It’s a metal that gives laboratory animals Alzheimer’s Disease.

It was named “Allergen of the Year” in 2022.

Producing it consumes 5% of America’s electricity.

Producing it releases 1.2 billion tons of greenhouse gases every year.

And it’s in your fridge.

Aluminum is a powerful neurotoxin. There’s good reason to believe it can cause adult dementia. More than 1 million American preschool children are allergic to it. And pulling it out of the ground burns through enough electricity to light every home and business in the entire United States.

Scientists are finding evidence of other health risks from overexposure to aluminum, and the list reads like the ending narration of a prescription drug commercial: cognitive and motor impairments, central nervous system toxicity, pulmonary fibrosis, asthma, calcium deficiency in bones, anemia, rare forms of muscle inflammation, and more.

Alzheimer’s Alert

Laboratory scientists in dozens of countries have been looking for ways to treat Alzheimer’s Disease for more than 50 years. When they find a chemical compound that looks promising, they test it on animals — after they give them the disease.

How do you give a lab animal Alzheimer’s Disease? Add aluminum salts to its diet.

And why not? It works. Rats respond well to aluminum chloride. With rabbits, aluminum maltolate is better. A search of the Google Scholar database reveals more than 5,600 scientific papers that mention “Aluminum-induced” Alzheimer’s. There were 584 in the year 2023 alone.

Alzheimer’s Disease is the sixth most common cause of death in the United States, so it’s important to know whether aluminum toxicity plays a role in its progression.

It gets worse: Aluminum in drinking water and other liquids causes inflammation in the brain. A team of scientists wrote in 2006 that the proteins associated with Alzheimer’s Disease and other dementias are built from components that the inflammation creates.

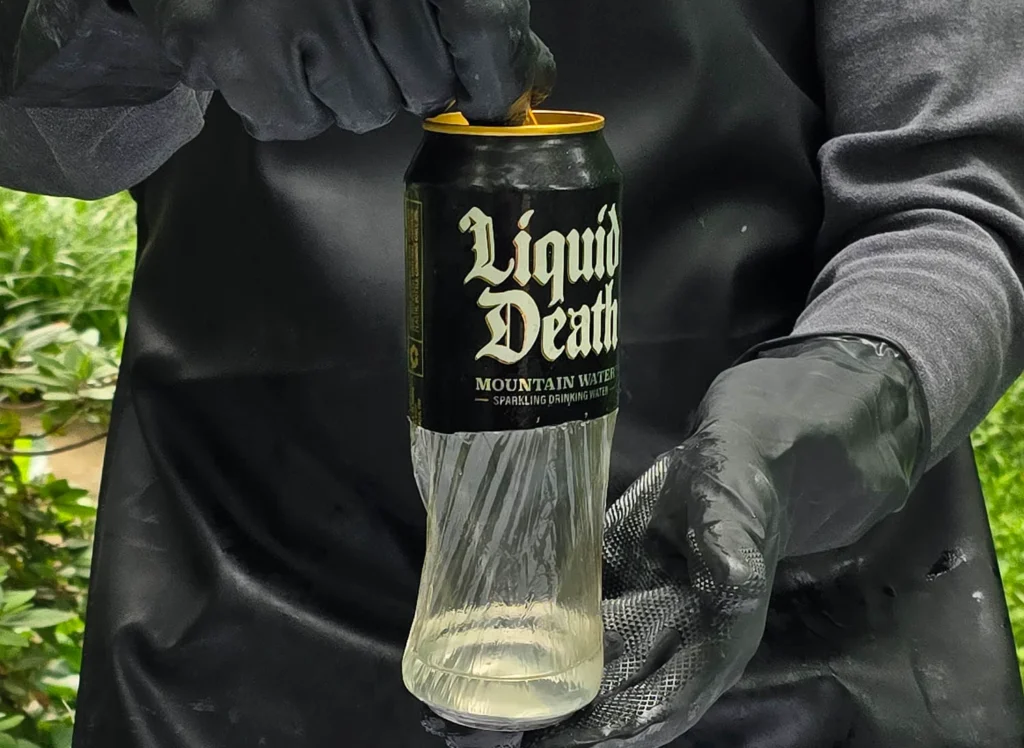

Partially dissolved aluminum can exposing the plastic liner

Did You Know?

Aluminum can companies know that when acids touch the neurotoxic metal, bits of it break free and float in your drink. That’s why they coat the insides of cans with a hazardous BPA epoxy.

Chicken Or Egg?

Did all that aluminum cause dementia? Or did dementia create the right conditions for the aluminum to accumulate? Researchers have been arguing since the 1970s about which comes first, but they tend to agree that severe dementia and an overload of aluminum in the brain go hand-in-hand. Even low levels of aluminum can interfere with other metals that normally assist with crucial brain functions.

Australian scientists wrote in 2019 about the impact on Alzheimer’s risk from “toxic metals including lead, aluminum, and cadmium.” They determined that there are more than 200 different reactions where these metals interfere with how cells keep the necessary balance of “essential” metals like copper, iron and zinc. Essential metals regulate energy metabolism and protect cells from bacteria, among other functions.

Did You Know?

The most reliable way to give Alzheimer’s Disease to laboratory rabbits and rats, before trying to treat them, is to add aluminum salts to their diet.

“Because of their high degree of toxicity, cadmium, lead and aluminum rank among the priority metals that are of public health significance,” the researchers concluded. “These metallic elements are considered systemic toxicants that are known to induce multiple organ damage, even at lower levels of exposure.”

Here’s how the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sums up the state of the science: “We do not know for certain that aluminum causes Alzheimer’s disease.” In the same paragraph, the agency confirms that “[s]ome studies show that people exposed to high levels of aluminum may develop Alzheimer’s disease.” The Alzheimer’s Association insists aluminum isn’t “confirmed” as a cause.

Some foundry workers in Indonesia would disagree. Scientists there published a study in 2022 that described what they found in men who work around aluminum. They sampled their urine after every shift, and then gave them cognitive tests. It turned out that 70 percent of them were impaired.

Allergic To Aluminum?

If you have a baby, a toddler or a preschooler, research data suggests that your child is more likely to be allergic to aluminum than to any food — including peanuts. Pediatricians and government scientists know this is a problem, but few parents have been told. That’s why a medical association called the American Contact Dermatitis Society named aluminum its “Allergen of the Year” in 2022.

American health authorities have known aluminum is an allergen since at least 1944, when a doctor published his research on “aluminum poisoning” among aircraft workers.

The good news is that allergists can perform a simple skin test to spot this allergy, and it’s the same test that they use to diagnose allergies to pets, pollen and tree nuts. Up to 5 percent of children who are tested are allergic to aluminum. The National Center for Health Statistics said in 2023 that food allergies affect 4.4 percent of children age 5 and younger, making it likely that aluminum allergies are more common in that age group.

This is a real problem, and not just because everything from drinking water to orange juice can come in an aluminum can. Childhood vaccines that prevent diphtheria, hepatitis and tetanus include an aluminum compound that makes the human body’s immune responses more powerful. (The fact that aluminum triggers an immune response in every child might also be a red flag.)

A team of German scientists described in 2020 how injections of that same aluminum compound can give lab rats asthma. This is similar to animal researchers using a different aluminum compound to stimulate Alzheimer’s Disease. So it shouldn’t be surprising that there’s a connection between aluminum-juiced vaccines and persistent childhood asthma. That news came in 2023 in a paper signed by more than a dozen researchers from the federal government and universities in Colorado and California.

The scientists wrote in the medical journal Academic Pediatrics that seven hospitals shared 327,000 children’s medical records for their research. Their bottom line? “In a large observational study, a positive association was found between vaccine-related aluminum exposure and persistent asthma.” What qualifies as “persistent” asthma? Two emergency room visits or one hospital stay, according to the authors, plus two or more long-term prescriptions for medicines that control asthma.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says it won’t change its recommendations about childhood vaccines based on new data about aluminum, but it calls the latest research a “potential safety signal.” Vaccinating children against crippling and deadly diseases is vitally important, and biomedical researchers are working on alternatives to aluminum.

Did You Know?

We use more than 180 billion aluminum cans every year, just for beer and soda. That’s 6,700 cans per second. And the EPA says more than two-thirds of them end up in landfills.

Energy Hogs & Toxic Sludge

It’s shocking but true: Domestic mining, refining and smelting aluminum — just that one metal — consumes 5 percent of all the electric power generated in America. If that sounds ridiculous, just ask Big Aluminum’s trade association, the Aluminum Institute. They admit it on their website.

For context, 5 percent of our electricity is enough to light every home and business in America. And we don’t have juice to spare: Power shortages in 2024 could affect as many as 300 million Americans and Canadians. Cryptocurrency mining and AI cloud computing have created new drains on the system. Summertime electricity demand in Virginia will increase five-fold in the next 15 years, and that’s not an outlier.

To make matters worse, the Aluminum Institute says there are “no viable alternatives” to the energy-hogging industry’s methods. Paying for electricity represents about 40 percent of the cost of bringing aluminum out of the ground and into the marketplace.

And a lot of that electricity is anything but green. The energy think-tank Ember said in 2019 that 64 percent of the power used to separate aluminum from its ore (in a process called electrolysis) comes from coal-burning power plants.

The nonprofit Environmental Integrity Project drew the same conclusion in a 2023 report, saying that while aluminum is part of the recipe for making solar panels, electric car batteries and windmills, most of the energy required to bring aluminum to market in the first place comes from burning fossil fuels.

“Domestic mining, refining and smelting aluminum — just that one metal — consumes 5 percent of all the electric power generated in America… the federal government’s Energy Information Administration says 5 percent of our electricity is enough to light every home and business in America.”

The scale of aluminum mining around the world is staggering. Here’s how a Columbia University “State of the Planet” report describes a single bauxite ore mine in western Guinea that extracts more than 98 million pounds every day:

Five to seven trains, each equipped with 120 wagons, leave that mine every day. Each wagon contains around 82 tons of bauxite ore, amounting to between 49,200 and 68,800 tons of bauxite shipped, by railway alone, daily. These are the operations of just one mining company and do not account for the truckloads of bauxite moving through the same territory each day.

That aluminum-rich bauxite ore also includes lead, cadmium, arsenic and low levels of radioactive uranium, thorium and radium. While the ore isn’t dangerous, the radioactivity is more concentrated in the main waste product from processing bauxite — a toxic sludge known as “red mud.”

Researchers determined in 2023 that 4.6 billion tons of the stuff are sitting in artificial lakes, underground containers and dried mounds around the world. And the aluminum industry dumps another 200 million tons each year.

Artificial reservoirs full of red mud have ruptured in the past. One example is the 35 million cubic feet of the caustic goop that flooded four Hungarian towns in October 2010. A six-foot wall of it destroyed everything in its path. Ten people died and 150 more were treated for chemical burns.

There are more than 700 U.S. patents for processes to recycle red mud and products that could use it. Yet the global aluminum industry only recycles 3 percent.

Trashing the Planet

Aluminum’s environmental problems cast a long shadow that reaches far beyond red mud and energy-hogging. The industry is responsible for releasing 1.2 billion tons of greenhouse gasses every year — along with overloads of several highly toxic chemicals.

One smelting plant in Indiana has been cited nearly 30 times since 2018 for discharging too much mercury into the Ohio River. (Its EPA permit allows more than a half-ton every year.) Together, America’s six smelters have racked up more than 200 federal violations for water and air pollution in the past six years.

That shouldn’t surprise anyone. The average age of those plants is 65, making them older than the Clean Air Act. A “grandfathering” loophole in the law exempts them from installing expensive “scrubbing” systems that remove deadly pollutants from exhaust before it’s belched out of a smokestack.

One of the worst problems is sulfur dioxide, a noxious gas that contributes to acid rain and heart attacks, and can cause rates of asthma to spike wherever people live downwind. Most of it comes from plants that process an oil-refinery waste product into a form of carbon that aluminum companies need to pull metal out of rock. Three such plants owned by a Texas company collectively spew 38,000 tons of sulfur dioxide into the environment every year.

Did You Know?

The aluminum industry admits that mining, purifying and smelting the metal consumes 5 percent of all the electricity generated in the United States. That’s enough to light every home and business in America.

“…most of the aluminum “recycled” every year consists of scrap metal recovered from smelting operations. Less than half comes from the sources we think of as recycling targets — like aluminum cans and foil….”

The big picture also includes the environmental devastation caused by strip-mining for bauxite ore, the most common source of aluminum. This kind of mining leaves a coat of iron-rich red dust on everything for miles around. It destroys forests and grasslands and pollutes water supplies.

Even though mining companies can get 50,000 metric tons of bauxite out of a single acre of land, they’re chewing up an area half the size of Manhattan every year to keep up with demand. In southwestern Australia, bauxite miners clear more land than logging companies.

A boom in electric vehicles will cause an even greater demand: Lightweight aluminum is needed to offset electric-car battery systems that can weigh nearly a ton. The blades of wind turbines are aluminum. So are the frames that hold up solar panels. But the industry doesn’t get to wear a green halo for starting a boom in renewable energy, according to the nonprofit Environmental Integrity Project, because most of the energy required to bring aluminum to market in the first place comes from burning fossil fuels.

And whatever they recycle, there’s a hidden cost to human health and the environment: cancer-causing chemicals. Dioxins and furans are toxic carcinogens, and aluminum recycling plants emit a lot of them into the atmosphere. They’re also what scientists call “persistent” pollutants, because it takes a very long time for them to break down into other, safer chemicals.

Nano-Aluminum

There’s a scientific revolution going on, and it’s too small to see with the naked eye. Nanoparticles, often smaller in diameter than 1/100,000 of a millimeter, are all around us — and much of this is a good thing. They’ve given us graffiti-proof wall coatings, odor-control socks, antimicrobial faucet handles and doorknobs, and chemicals that neutralize environmental contaminants. And if your mobile phone is ever miniaturized to the point where you can carry it under your skin, careful arrangements of metal nanoparticles will be storing the data.

Some medical researchers are even delivering drugs to specific parts of the human body by using nanoparticles as carriers. At their tiny size, the particles are small enough to slip through the pores in blood vessels but not so small that they clump together. They’re also often made of aluminum oxide.

Aluminum now represents 20 percent of the global nanoparticles market. Military contractors are using it as a controlled accelerant in solid rocket fuel combustion. It’s beginning to make artillery shells and other explosives more powerful and deadly.

As aluminum nanotechnology becomes more advanced, there will be more of these particles everywhere — including in the air we breathe. They’re 1,000 times as tiny as the pores in our lung tissue, and 1/100th the size of the biggest molecules that can slip through the barrier between blood vessels and the human brain.

Since aluminum deposits in the brain are closely associated with Alzheimer’s Disease and other forms of dementia, we could be setting ourselves up for a wave of cases that will be impossible to diagnose for decades.

Did You Know?

Scientists showed in 2006 that aluminum in drinking water can cause inflammation in the brain. And not just any inflammation: the kind that creates proteins associated with Alzheimer’s Disease and other dementias.

Too Shiny To Fail?

Geologists call aluminum an “everywhere metal,” since it’s the third-most abundant element in the earth’s crust (after oxygen and silicon). It’s lightweight and strong, making it useful for food and beverage cans, foils, cooking utensils, food processing equipment, beer kegs, cars, airplane parts, building materials, window frames, major appliances, electrical conductors, and much more.

But what if there were a scientific consensus that aluminum is the next asbestos or lead? What if we agreed that we should be taking it out of circulation instead of embracing it more every year? Could we even do that?

Or is Big Aluminum “too big to fail,” like mega-banks and car manufacturers whose collapse would crush the U.S. economy?

Our overall exposure to the toxic material — what doctors call our “body burden” — comes from dozens of places. Some of them would be easier to replace than others. It may be time to start trying.

Aluminum enters the human body from food additives like preservatives, fillers, coloring agents, anti-caking agents, emulsifiers and baking powders. An aluminum compound keeps grated and shredded cheese from clumping together in grocery packages. High aluminum concentrations have been found in shrimp, mussels, fruit juices, wine, coffee, beer, meat, rice, cereals, potatoes, fruits, green and yellow vegetables, pasta, pastries and cakes.

Most powdered infant formula mixes are contaminated with aluminum too. (The highest levels show up in soy-based, lactose-free, and hypoallergenic versions.) The plant that gives us black tea accumulates aluminum naturally, although tea also contains an ingredient that might bind with it so our stomachs can’t digest it.

We get a small amount of aluminum from the air we breathe, and that pollution level can skyrocket around mines, refineries and smelters that process the metal. Your favorite antiperspirant and antacid probably list an aluminum compound as their main active ingredient.

Automakers and building contractors are never going to give up aluminum’s obvious assets, but there are small changes that we all can make. Aluminum cans that serve our soda and beer use more aluminum than any other business sector.

No, Big Aluminum isn’t too big to fail. But companies that use it when there are viable alternatives available should consider making a U-turn.